reading-notes

Code Fellows reading notes

Structure Web Pages with HTML

Wireframe and Design

The Definitive Guide: How to Make Your First Wireframe

A Introduction to Wireframing

What is a Wireframe?

Wireframing is a practice used to define and plan the information hierarchy of a website, app, or product design. In the wirefram when designing a screen you do a black and white diagram before building anything with code. This lets you plan the layout and interaction of your interface.

Wire Frame Examples

Some people like to draw their wireframe by hand, others like to use software like Invision, or Balsamiq to create theirs.

Tools fo Wireframing

-

UXPin: UXPin has a wide range of functionalities, but one of the best ones is how it facilitates building responsive, clickable prototypes directly in your browser.

-

InVision: InVision allows you to get feedback straight from your team and users through clickable mock-ups of your site design. It’s completely free.

-

Wireframe.cc: Wireframe.cc provides you with the technology to create wireframes really quickly within your browser, the online version of pen and paper.

6 Steps to Make a Wireframe

-

Do your research

-

prepare your research for quick reference

-

Make sure to have your user flow mapped out

-

Draft, don’t draw. sketch, don’t illustrate

-

Add some details and get testing

-

Start turning your framework into prototype

3 Principles on How to Make Your Wireframe Good

-

Clarity: Your wireframe needs to answer the questions of what that site page is, what the user can do there, and if it satisfies their needs.

-

Confidence: Ease of navigation through your site and clear calls-to-action increase user confidence in your brand. If your site page is unpredictable, or has buttons or boxes in unexpected places user confidence diminishes. A lot of this information can already be organized at the wireframing stage. Using familiar navigational processes and placing buttons in commonly-used and intuitive positions, user confidence

-

Simplicity is key: Too much information, copy, or links, can be distracting to the user and will have a detrimental affect on your users’ ability to achieve their goals. You want your users to be able to find their way through your site with as little extra ‘fluff’ as possible, to the elements that map to their most significant goals in a given context.

HTML Basics

What is HTML (HyperText Markup Language)

it is a code lanngauage use to structure a web page and its content. consists of a series of elements, which you use to enclose, or wrap, different parts of the content to make it appear a certain way, or act a certain way. The enclosing tags can make a word or image hyperlink to somewhere else, can italicize words, can make the font bigger or smaller, and so on.

Example: to write a paragraph that says “I live on a beautiful island” the the code element would be <p>I live on a beautiful island</p>.

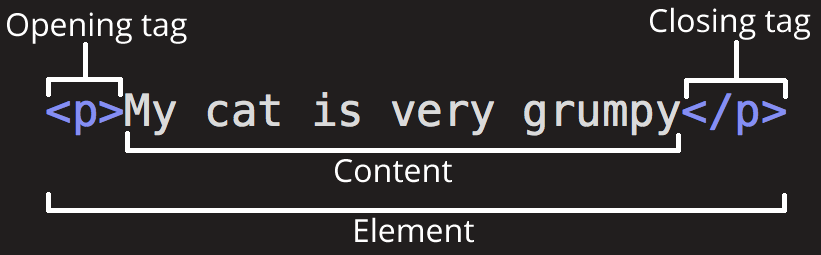

Anatomy of an HTML element

-

The opening tag: This consists of the name of the element (in this case, p), wrapped in opening and closing angle brackets. This states where the element begins or starts to take effect — in this case where the paragraph begins.

-

The closing tag: This is the same as the opening tag, except that it includes a forward slash before the element name. This states where the element ends — in this case where the paragraph ends. Failing to add a closing tag is one of the standard beginner errors and can lead to strange results.

-

The content: This is the content of the element, which in this case, is just text.

-

The element: The opening tag, the closing tag, and the content together comprise the element.

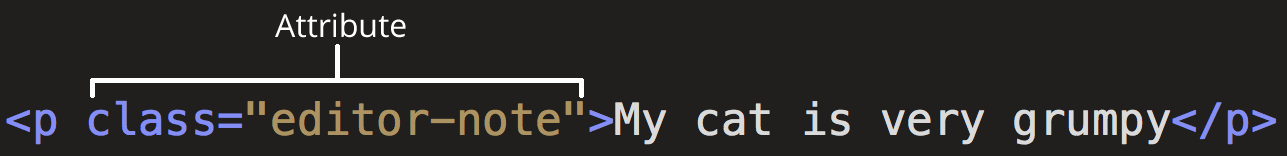

Element with Attribute

Anatomy of an HTML document

Link to the Anatomy of an HTML Document

Images

The image element in HTML IS:

<img scr="images/firefox-icon.png" alt="My test image">

Marking up text

headings

-

<h1>Main title</h1> -

<h2>Top level heading</h2> -

<h3>Subheading</h3> -

<h4>Sub-subheading</h4>

Paragraph

Element: <p>This page is about class 4 HTML</P>

Lists

The two main list elements are ordered lists or unordered lists, which after selecting the list element, each item inside the lists is put inside a (list item) element.

-

Ordered List:

<ol> -

Unordered List:

<ul> -

List item:

<li>

LINKS

Example: <a href="https://www.html.know/en-US/howto/learninghhtml/">How to Learn HTML</a>

The source of all the notes and images from this HTML article

Sematics

In programming, Semantics refers to the meaning of a piece of code — for example “what effect does running that line of JavaScript have?”, or “what purpose or role does that HTML element have” (rather than “what does it look like?”.)

Sematics in JavaScript

In JavaScript, consider a function that takes a string parameter, and returns an <li> element with that string as its textContent. Would you need to look at the code to understand what the function did if it was called build('Peach'), or createLiWithContent('Peach')?

Sematics in CSS

In CSS, consider styling a list with li elements representing different types of fruits. Would you know what part of the DOM is being selected with div > ul > li, or .fruits__item?

Sematics in HTML

In HTML, for example, the <h1> element is a semantic element, which gives the text it wraps around the role (or meaning) of “a top level heading on your page.”

The source for all the information presented in this article about sematics